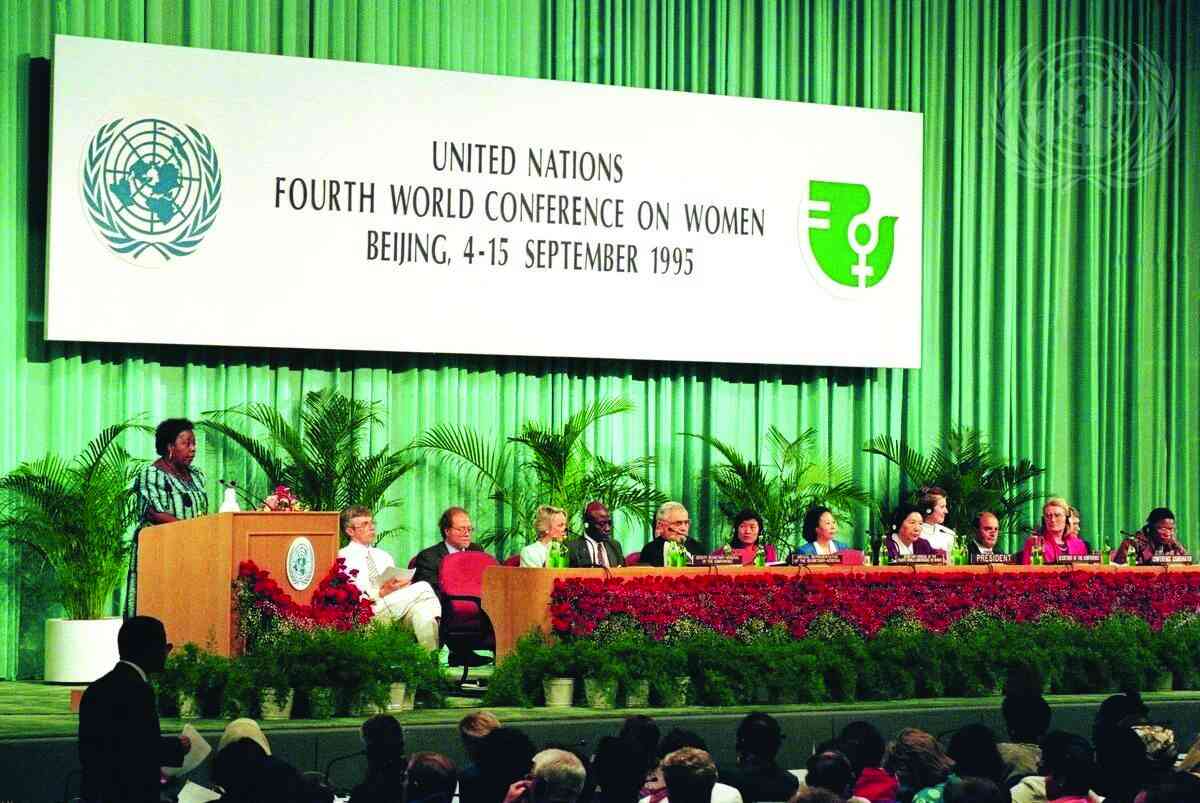

THIS year, the International Women’s Day coincides with the commemoration of the 30th anniversary of the Beijing Platform of Action.

This is an agreement that was adopted in 1995 at the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing. Most of us will remember how suddenly our mothers and grandmothers’ vocabulary changed where the term, “Beijing” started to mean “women’s rights”.

It was used both as a feminist rallying call for my grandmothers’ generation — although they would not have referred to themselves by the ‘F-word’ — and as an insult by patriarchal society to refer to women who were, “defiant and out to destroy family values and traditional norms”.

In case you got lost in translation dear reader, ‘family values and traditional norms’ is euphemism for women oppression.

Even the Republican Party in the United States, fronted by trigger-happy MAGA, still use the same euphemism to mean exactly what it meant in my village back then — the continued subjugation of women.

The women’s rights movement has a long a proud history of struggle. It has been a century since the fight for gender equality gathered momentum post-World War 1 as advocacy for women’s voting rights made significant and widespread gains.

But we still need 100 and 34 years more to achieve gender equality as the World Economic Forum asserts in their Global Gender Gap Report.

The spirit of Beijing–state feminism

- Promise of state feminism deceptive

Keep Reading

The Beijing Conference’s emphasis was on women’s political participation and representation in decision-making, legal and institutional reforms to address gender-based discrimination as well as economic empowerment and equal pay for women.

It also pushed reproductive rights and healthcare access. State policies, laws and institutions had to change to address these issues.

While these goals were ambitious and sought to challenge male dominance in society, they did not fundamentally question or seek to dismantle the patriarchal structure of the state itself.

Instead, the Beijing agenda aimed to integrate women into state power, assuming that inclusion alone would lead to equality. This led to governments creating women-focused policies and institutions.

Zimbabwe and many other countries have women’s ministries, gender departments, commissions and desks and even banks focused on women.

Zimbabwe’s constitution even goes on to guarantee 50/50 gender representation in all facets of society. All these can be traced back to the spirit of Beijing which, whether intentionally or inadvertently birthed state feminism.

I know this all sounds well and good, but my cynic self sees this as an oxymoron. It is the same state that has since its advent, institutionalised patriarchy. Excuse me, but I have to ask: Can the state be truly feminist?

The state is a patriarchal construct

I subscribe to the idea that the state, as a political and social institution, is fundamentally shaped by and reinforces patriarchal power structures. This means that the state is not a neutral entity but one that often upholds male dominance.

Before you protest dear reader, let me take you through the origins of the state.

The character of the state can be viewed from the social conditions that necessitated its formation as Thomas Hobbes contends that states emerged from the need to escape the “state of nature”, where life was “nasty, brutish, and short”.

As such, the formation of states has often been linked to “war-making, conquest, and the monopolisation of violence”, as renowned American sociologist and political scientist Charles Tilly contends.

He even coined the famous aphorism “war made the state, and the state made war”.

All states, including the Zimbabwean state arose through organised violence, coercion and consolidation of power.

These processes historically created and positioned male warriors and rulers, in both governance and social structures thereby institutionalising male dominance.

This shows clearly how state formation was deeply patriarchal resulting in the exclusion of women from the military and politics and the regulation of women’s roles to reproduction and domestic work to sustain the state’s war economy.

The formation of the state has always been inherently gendered from its inception.

The African state is deeply colonial

Like all states, the colonial state was built through violence, and this militarised structure carried over into post-colonial governance.

This brings to the fore, the conception of the coloniality of power and gendered oppression.

Decolonial feminists argue that militarism, capitalism, and patriarchy are interconnected, as the state prioritises war, policing, and resource extraction over social welfare and gender justice.

For instance, post-colonial African states maintain social and political structures inherited from colonial rule.

These structures are patriarchal and often reinforcing conservative gender roles in nationalism and state-building projects.

The modern nation-state, shaped by European colonialism, absorbed and reproduced colonial gender norms.

Viewed from this lens, I am tempted to ask again: Can the state be feminist?

State feminism carries false promise

There is nothing wrong with the state taking up its responsibility to its citizens by ensuring social justice and gender equality.

The problem arises in the reality that despite all the laws, policies, institutions and commitments that the state has made towards gender equality in the past 100 years, we still need another 134 years to achieve it.

The disturbing reality is that women’s representation remains low, where it seems high, it is often hollow and tokenistic.

They are still largely excluded from meaningful social and economic participation.

Women’s rights and bodies are still subject to social and political control by the same state that purports to be feminist.

You see, the problem of state feminism is that it appropriates the legitimate struggles for women’s rights, highjacks the feminist’s agenda and co-opts its key figures.

It then depoliticises gender equality and demobilises the feminist movement moving it towards safer conversations, which do not have much potency when challenging the patriarchal state of our society.

Dilution of feminist language

State feminism does not only appropriate feminist struggles, it also dilutes the radical language of activism to make it more palatable to state institutions while avoiding deep structural change.

One of the most significant ways this has happened is through the bureaucratisation of feminism, particularly with the rise of gender mainstreaming.

Initially a strategy to integrate feminist concerns into state policies, gender mainstreaming quickly became a technical exercise focused on policy language rather than political transformation.

Instead of dismantling patriarchal structures, it shifted feminist demands towards softer, more acceptable terms like “gender equality” and “women empowerment”, while ignoring critiques of capitalism, militarism, and state violence.

Let’s focus on “women’s concerns”

Another way state feminism has weakened feminist activism is through the push for women’s political representation without changing the patriarchal nature of politics and governance.

While gender quotas have increased the number of women in parliament and government, this inclusion has not necessarily translated into feminist policymaking.

Many female politicians are forced to align with party interests rather than challenge oppressive structures, and the issues framed as “women’s concerns” are often limited to health and education and livelihoods, sidelining more radical demands for land rights, economic justice, and state accountability.

In Rwanda, for example, the government boasts the highest percentage of women in parliament, yet feminist critiques of authoritarian governance remain silenced.

Empowerment is a snake oil solution

The language of feminism has also been transformed from a radical call for liberation to a depoliticised notion of “women’s empowerment”.

Where early feminist movements sought to dismantle patriarchal and capitalist systems, contemporary state feminism promotes an individualistic model of empowerment that focuses on self-improvement rather than structural change.

This shift is evident in the rise of neoliberal feminism championed by institutions, such as the World Bank and United Nations Women, which promote women’s entrepreneurship as a solution to gender inequality, while ignoring deeper issues like fair wages, land redistribution, and social protection.

Within a patriarchal state and economic architecture, empowerment remains a seductive snake oil solution that has no transformative value.

Laundering the authoritarians image

The creation of ministries for women’s affairs and gender commissions has further institutionalised feminism in ways that strip it of its activist roots and political potency.

While these bodies are meant to advance gender equality, they often focus on non-threatening, incremental reforms rather than addressing state violence, economic inequality, or social control.

Moreover, they are frequently underfunded, politically sidelined, or used to discipline feminist activists.

Perhaps the most concerning use of state feminism is when it becomes lipstick on a pig to launder the image of authoritarian regimes and justify their power while suppressing dissent.

In some cases, women’s rights are selectively promoted to serve the interests of the state, allowing governments to present themselves as progressive while ignoring broader issues of repression, violence, and economic injustice.

The sober view

While Beijing expanded women’s participation, it did not challenge the patriarchal foundation of the state.

It was a major victory for women’s rights within the existing system, but for those seeking a radical transformation of the state, it fell short of dismantling systems of male dominance.

Ultimately, state feminism is a deceptive promise that has turned feminist struggles into policy reforms that make governments appear progressive without addressing the root causes of oppression.

By focusing on representation rather than transformation, individual empowerment rather than collective liberation, and soft policies rather than structural challenges to patriarchal capitalism and state violence, state feminism neutralises the revolutionary potency of feminist activism.

Real feminist activism continues to thrive in grassroots movements, labour struggles, land rights activism, and direct action against state violence, rather than in government policies designed to make feminism more acceptable to the status quo.

One nagging question in my analysis is, “can the state be feminist?” echoing Audre Lorde’s famous statement: “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house”.

Lorde argued that we cannot use the same systems, structures, and ideologies that uphold oppression to achieve liberation.

If the state, capitalism and patriarchy are the master’s house, then relying on their tools — such as legal reforms, representation in elite spaces, and inclusion in state institutions — will not lead to true liberation but rather to co-optation.

What is clear is that without structural change to transform state patriarchy, then state feminism remains simply its evil twin. Insidious in its deception! But let us talk again in 134 years!

This is my sober view; I take no prisoners.

- Dumani is an independent political and development thinker. He writes in his personal capacity.