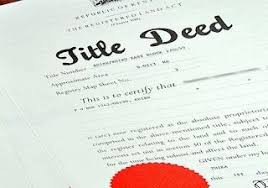

THE Farm Title Deed Programme was launched recently by the Zimbabwean government at the tail end of 2024.

It heralds a new era going into 2025 as it represents a bold and pivotal step in addressing one of the country’s most enduring challenges: land ownership and utilisation.

Land, in Zimbabwe, is far more than a physical asset; it is an emblem of sovereignty, liberation, and economic potential. This initiative seeks to transition beneficiaries of the land reform programme into formal landholders, offering title deeds that promise tenure security and financial empowerment. Yet, as with any ambitious policy, its implications extend far beyond the surface.

For policymakers, academics, and property stakeholders, the programme invites a critical appraisal. Will it catalyse a new era of agricultural productivity and financial inclusion, or will it remain a symbolic gesture constrained by bureaucratic and economic realities?

This analysis dissects the programme’s promises and potential pitfalls, examining its historical resonance, economic ambitions, and structural challenges. By engaging with these dimensions, we aim to provide a nuanced understanding of whether this initiative can deliver tangible transformation or merely formalise existing realities.

The following critique seeks to illuminate these complexities, offering deep insights for stakeholders at the highest levels of academia, industry, and governance.

Historical context, significance

Land ownership in Zimbabwe is steeped in historical conflict and profound socio-political importance. For over a century, colonial expropriation deprived the indigenous population of their ancestral lands, leading to resistance movements such as the First Chimurenga.

- Travelling & touring: Stirring the hornet’s nest

- Power of language in nation building

- Language: A glue that binds nations

- Farm Title Deeds Programme bold step

Keep Reading

The Second Chimurenga culminated in independence in 1980, followed by the land reform programme in the 2000s. The reform programme, though achieving a form of restitution by redistributing land to black Zimbabweans, was criticised for inadequate planning, loss of agricultural productivity, and tenure insecurity.

The Farm Title Deed Programme seeks to address these historical grievances, while ensuring that redistributed land becomes a catalyst for economic development.

By issuing formal title deeds, the government attempts to correct one of the most critical gaps in the land reform programme: the absence of legally recognised and bankable ownership.

The policy symbolises an effort to move beyond the ideological rhetoric of land reclamation to the practicalities of land utilisation.

For example, under the previous 99-year lease system, farmers often struggled to access financing because banks were reluctant to lend against state-controlled leases.

The new policy seeks to resolve this by providing documents that could potentially be used as collateral. However, it is worth noting that the deeds are issued under the continued framework of state land custodianship, which could limit their efficacy.

Historically, attempts to balance national ownership with individual empowerment have faced challenges, such as in South Africa, where similar tenure systems failed to spur significant rural investment.

Zimbabwe’s ability to learn from these precedents will be critical in determining the success of this initiative.

Dynamics: Stability or continuity?

One of the primary objectives of the Farm Title Deed Programme is to provide landholders with security and permanence. In theory, the issuance of title deeds transforms informal or temporary land allocations into legally recognised ownership.

This offers beneficiaries — estimated at 23 500 A2 farmers and 360 000 A1 farmers — a stronger sense of control and autonomy over their land.

However, the programme raises questions about whether this formalisation represents a substantive change in ownership dynamics or merely institutionalises the status quo.

Many beneficiaries of the land reform programme already operated under informal or semi-formal tenure arrangements, which allowed them to farm but left them vulnerable to disputes or government repossessions.

The new title deeds are designed to resolve these vulnerabilities, but their real-world impact depends on the clarity and enforceability of their terms.

For instance, the deeds’ restriction to “qualifying Zimbabweans” ensures that land remains under local control, reflecting the government’s commitment to preserving the gains of the liberation struggle.

However, this limitation could stifle the broader economic benefits of a competitive and open land market. A farmer holding a title deed may find it difficult to sell or transfer the land, limiting liquidity and flexibility.

In practical terms, this means that while ownership appears more secure, it is also less dynamic. Zimbabwe’s past attempts to introduce controlled tenure, such as through the fast track land reform, led to bottlenecks in market activity. Without clear mechanisms for transfers and dispute resolution, the title deeds could become symbolic rather than transformative.

Economic empowerment potential

Central to the government’s pitch for the farm title deed programme is the notion that secures land tenure will unlock access to credit and spur investment in agriculture.

Farmers, who hold formal deeds, it is argued, will be able to use their land as collateral to secure financing for inputs, machinery, and expansion. This could lead to increased productivity and profitability, particularly for smallholder farmers.

In practice, however, the economic empowerment potential of this initiative depends on the willingness of financial institutions to recognise the title deeds as viable collateral.

For example, Zimbabwean banks may remain cautious due to the deeds’ state-controlled framework. A precedent exists in which banks were reluctant to accept 99-year leases because these were tied to state approval.

If similar reservations persist, the programme may fail to deliver its intended financial benefits.

Moreover, the broader macroeconomic context presents additional challenges. Zimbabwe’s history of hyperinflation and currency instability undermines the viability of long-term financial planning.

Even if farmers secure loans, the cost of servicing them could become prohibitive in a volatile economic environment. In countries such as Kenya, where secure land tenure has led to significant agricultural growth, stability in governance and financial systems played a key role. Without similar conditions in Zimbabwe, the deeds may not yield the anticipated economic upliftment.

Transactions, market implications

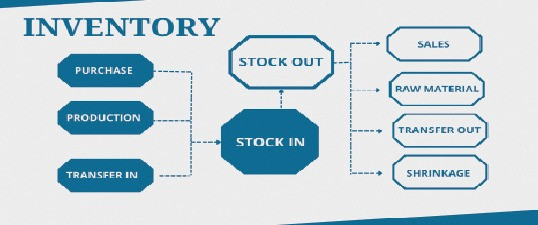

The introduction of title deeds formalises land ownership, which theoretically increases the stock of recognised land assets, despite the fact that sales have been happening informally with change of ownership taking place through the regularisation of the offer letters.

The issuance of title could enhance transparency and accountability in the land sector, particularly for policymaking and investment purposes. However, the impact on market activity is likely to be less pronounced due to the restrictive transferability of these deeds.

Restrictions on the sale of land to non-qualifying individuals or entities ensure that ownership remains within a localised framework, safeguarding the objectives of the land reform programme.

However, these restrictions may also suppress the dynamism of the land market. For instance, a farmer wishing to sell land to fund retirement or other ventures may find the pool of eligible buyers limited, reducing the land’s market value and liquidity.

Additionally, state oversight of transactions introduces another layer of complexity. Historical examples from Zimbabwe and beyond show that overregulation often deters investment.

In Ghana, for example, the cumbersome land acquisition process discouraged foreign direct investment in agriculture, despite reforms intended to boost ownership security.

Zimbabwe risks replicating this issue if the transfer and valuation of title deeds remain bureaucratically encumbered.

Inclusivity, equity in implementation

The programme’s stated inclusivity goals are laudable, with specific provisions targeting women, youth, and war veterans. These groups have historically faced barriers to land access, and the issuance of title deeds could serve as a corrective measure.

For example, women — who constitute a significant proportion of Zimbabwe’s agricultural workforce — often lack formal recognition of their land rights. The programme’s emphasis on gender inclusion could help bridge this gap.

However, effective implementation is crucial to achieving these equity goals. Zimbabwe’s history of administrative inefficiency and allegations of favouritism in land allocation pose risks to the programme’s credibility.

- For instance, the fast track land reform programme was criticised for disproportionately benefiting political elites, leaving smallholder farmers marginalised. Ensuring that the distribution of title deeds is fair, transparent, and impartial will be key to avoiding similar pitfalls.

Moreover, the practical benefits of ownership must extend beyond symbolism. A woman receiving a title deed, for example, must also have access to training, markets, and financial resources to maximise her land’s potential.

Without such support, the title deed becomes a hollow document, failing to deliver meaningful empowerment.

Conclusion: Promise or symbolism?

The Farm Title Deed Programme is a landmark initiative that encapsulates both the aspirations and challenges of Zimbabwe’s evolving land policy. At its core, the programme seeks to rectify the historical inequities of land ownership while creating a framework that enhances agricultural productivity and financial empowerment.

However, its success will hinge on the clarity of its legal structures, the robustness of its implementation, and the stability of the broader economic environment.

For property stakeholders, the programme offers both opportunity and caution. While it provides a pathway toward formalising ownership and unlocking economic potential, questions about transferability, financial market engagement, and equitable access remain critical.

Its capacity to deliver transformative outcomes will depend on whether it transcends symbolism to achieve genuine empowerment and investment. If executed with precision and fairness, the Farm Title Deed Programme could stand as a pillar of Zimbabwe’s Vision 2030.

If not, it risks becoming another chapter in the nation’s complex land narrative, marked more by promise than realisation.

- Juru is the chairperson of the Green Building Council of Zimbabwe and the chief executive officer of Integrated Properties. — +263 773 805 000.