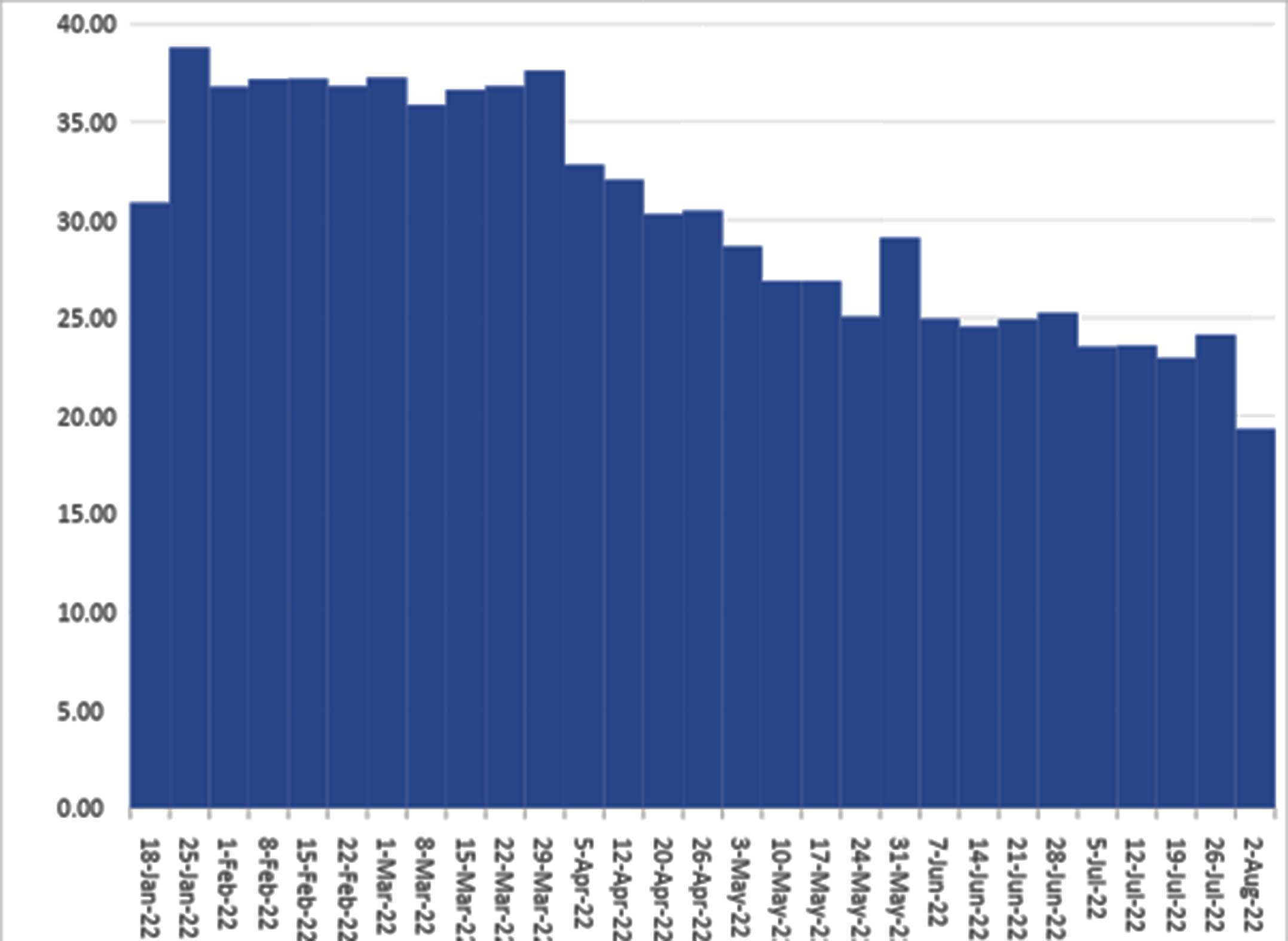

By Respect Gwenzi A MAJOR highlight of this week’s auction market trading activity is the total amount of forex exchanged. At US$19,3 million, the total value of auction flows this week ranks as the lowest allotment since December 2020.

The low allocation is not in isolation, it follows a protracted decline stretching from the beginning of the current year.

The average weekly allocation for the whole of 2021 was US$40,1 million, implying that the weekly allocation has declined by over 50% from prior year.

At peak, the auction market exchanged US$52 million in a session in July 2021. From the July peak levels, the weekly allocation has declined by 63% based on the latest week’s performance.

Is this a big deal? Yes it is. The amount allocated per week is a reflection of supply, inasmuch as it may also reflect on demand. The overall picture points towards dwindling supply levels on the auction market.

This is a worrying trend. The auction market is the main open market for the exchange of forex and if supply is dwindling there is high risk of market failure.

However, there are many other factors at play which could be influencing the levels of auction market trades.

The government resolved to settle a portion of dues to its contractors in foreign currency and this allocation means the contractors do not have to come to the market directly. The resources which would otherwise have been directly traded on the market are exchanged via forex payments. However, this reduces competitive bidding.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

Gold coins

The other reason why forex trades may be coming off on the auction market is the advent of gold coins. The government has set aside a forex allocation for the procurement of gold and the production of gold coins.

This means that forex, which was meant to be supplied on the forex market is reduced on one hand and the local currency which was meant to bid forex on the respective market is partially redirected towards gold coins purchases.

There is partially a compensatory effect in terms of forex redirected and local currency redirected, for the purpose of gold coins purchase.

However, much of the money chasing gold coins is institutional driven and most of it coming from pension funds, asset management firms, operating companies with high levels of cash holdings.

This group of spenders are not typical auction market participants and thus the compensatory effect is only in part. If it is true that a significant portion of the coins will be snapped up by investment related entities who are not necessarily auction market participants, it would follow that the demand for forex either on the auction or parallel market will remain high.

The decline in weekly allocation comes on the backdrop of a huge leap in forex earnings as measured by exports by value. Zimbabwe’s exports for the first six months of the year swelled by over 25% to about US$3,5 billion, its highest ever.

It is projected that exports will reach US$7,2 billion for the full year and if this is attained, the outturn will be an all-time high. It would be expected that if inflows swell, all else being equal, supply of forex on the market will increase rather than decrease.

However, this justifies the earlier assertion that flows are being channelled elsewhere as the government attempts to circumvent the drastic depreciation of the local currency.

The dangers of rechannelling into isolated sectors or segments is that distortion may arise and these promote arbitrage opportunities, the cost of which will be a worse off outturn in the currency over the mid-term as well as rising debt on government’s books. The panacea to a depreciating currency is removal of censures on the currency market.

The currency market needs to be fully liberalised. US$7,2 billion per annum deduces to US$150 million a week, way above the US$20 million present auction allocation.

If the government is sincere that the levels of money supply are as reflected at ZW$1 trillion, this will deduce to a mere US$2,2 billion at present auction market rates and this means about US$500 million can clear the excesses of money supply.

The only possible reason why the government is not willing to fully liberalise the market is because it may not trust itself with money supply.

The government, as we have known it, has the propensity to issue currency and borrow in an extraordinary way, such that money supply will blow out of proportion.

The price the government pays for retaining a grip on the auction market is the huge parallel market premiums and the inflation, which follows a weakening currency.

- Gwenzi is a financial analyst and MD of Equity Axis, a financial media firm offering business intelligence, economic and equity research. — [email protected]