ON February 2, 2025, I decided to pass through Food Lovers Honeydew to buy a few groceries — to be specific, two items, drinking water and dog food.

When I arrived at the entrance, the pay queue was overflowing to the entrance of the shop. There was also a long queue to get inside the shop.

As a person who enjoys utilising their senior citizen benefits, which are respected at this particular shop, I walked up to the front of the queue, grabbed a trolley and two cases of water and asked if I could be let in to grab the dog food and leave.

I was told that the shop was insanely full and I had to go to the pay points via the exit.

In fact, one Food Lovers shop assistant kindly took my trolley and we entered the shop via the exit so that I could access a pay point. A young lady helping at the pay point rushed into the shop to collect some dog food for me and a small bottle of orange juice, as I was thirsty.

What begs an answer is, here is a formal retailer, bursting at the seams with customers and yet the generality of the formal retail sector in Zimbabwe is collapsing all around us, why? Why are other formal retail shops failing and Food Lovers, Honeydew thriving?

There is not one answer to this issue. The answer is multi-faceted and includes but is not restricted to the following: Poor customer service, mismanagement through the payment of high executive perks in an environment where frugality and cutting back should be instituted, poor buying practices and corruption within buying departments of formal retail shops, failure to understand the winds of change, uncompetitive pricing, on the vegetable and bakery side — non fresh food on offer, etcetera.

The informal sector, specifically the tuckshops, are being blamed for the collapse of the formal retail sector. If we assume that this is the only reason, which it is not, why have the formal retail chains not transformed into mega wholesalers such as Makro or Jumbo in South Africa?

- TSL profits slow as costs escalate

- Great Limpopo trans-frontier conservation area ministers meet

- TSL profits slow as costs escalate

- All set for Madzibaba 29th album launch

Keep Reading

Why has OK Mart in Hillside that was mimicking Makro or Jumbo failed in Zimbabwe?

There is more than meets the eye. This issue is layered. In this instalment, we are looking at why government should not tamper with market forces. The only way to encourage the informal retail sector to become the formal retail sector, is to support not manufacture unrealistic policies to crowd it out!

In jaundiced efforts to stabilise the economy and formalise the informal retail sector, governments may be tempted to intervene in supply chains and value chains. The recent directive from Zimbabwe’s Finance, Economic Development and Investment Promotion minister Mthuli Ncube, which mandates suppliers to bypass the informal sector in favour of wholesalers and formal retailers, exemplifies such interventions.

While the intention may be to regulate the economy and support formal retail, this approach is fraught with risks and detrimental consequences. Here are several reasons why government intervention in supply chains and value chains can be harmful, particularly in the context of Zimbabwe’s retail sector.

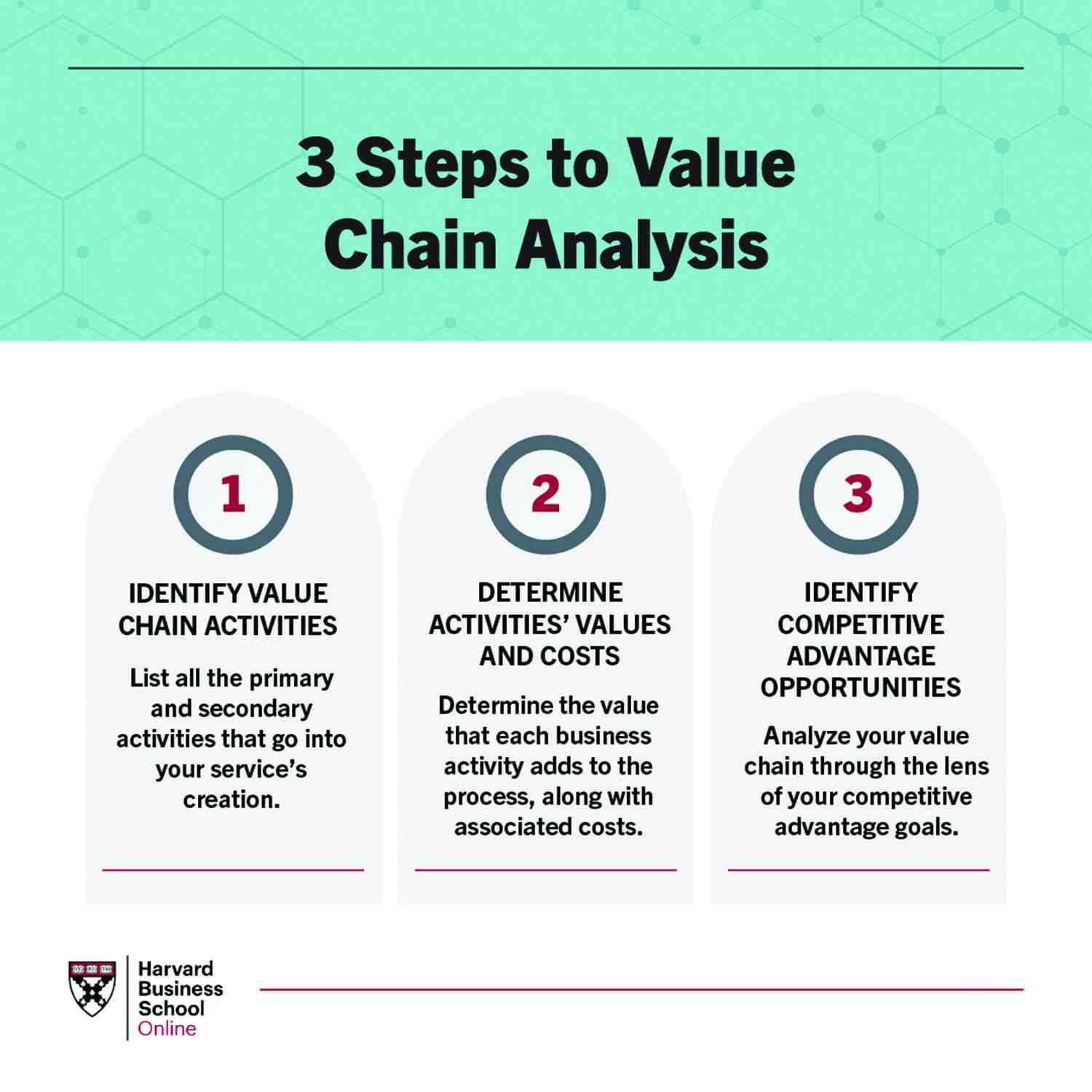

But first, let us unpack the difference between supply and value chain. The concepts of supply chain and value chain are both critical in business management, but they focus on different aspects of how companies operate and create value.

Here are the key differences:

Supply chain

It encompasses all the processes involved in the production and distribution of goods and services. It includes the flow of materials, information, and finances from suppliers to manufacturers to wholesalers to retailers and finally to the end consumer.

The primary focus of the supply chain is on the efficient movement and management of products and materials. This includes procurement, production, logistics, and distribution.

Major components include suppliers, manufacturers, warehouses, transportation systems, and retailers.

The main goal of the supply chain is to maximise efficiency and minimise costs while ensuring that products are delivered to customers on time. Supply chain management involves coordinating and optimising the various functions and activities to improve overall performance and responsiveness to market demands.

Value chain

It refers to the series of activities that a company performs to deliver a product or service to the market. It includes all the steps from conceptualisation to after-sales service, focusing on how each activity adds value to the product.

The primary focus of the value chain is on creating value for customers at every step, emphasising differentiation and competitive advantage. Major components include inbound logistics, operations, outbound logistics, marketing and sales, and service.

It also includes support activities such as firm infrastructure, human resource management, technology development, and procurement. The main goal of the value chain is to create a competitive advantage by delivering greater value to customers, either by offering lower prices or by providing more benefits that justify higher prices.

Value chain management involves analysing and optimising the activities to enhance value creation, often through innovation, quality improvement, and customer engagement.

While the supply chain focuses on the logistics and efficiency of moving products, the value chain emphasises the creation of value through various business activities. Both are essential for a company’s success, but they serve different strategic purposes.

Here are nine reasons why government intervention in supply chains and value chains can be harmful, particularly in the context of Zimbabwe’s retail sector.

Market dynamics disruption

Supply chains and value chains operate best when they are allowed to function freely within the parameters of supply and demand. Government intervention disrupts these natural market dynamics.

By mandating that suppliers avoid the informal sector, the government is effectively distorting the market. This interference can lead to inefficiencies, as suppliers may face new challenges in meeting the demands of formal retailers without the flexibility that the informal sector provides. The result can be shortages, higher prices, and a decrease in consumer choice.

Informal sector marginalisation

The informal sector, including tuckshops and small vendors, plays a vital role in many economies, especially in developing nations such as Zimbabwe. These businesses often serve as a lifeline for communities, providing employment and essential goods at accessible prices.

By side-lining the informal sector, the government risks marginalising these businesses further, pushing them into deeper economic hardship, and exacerbating poverty levels. Instead of supporting the transition of informal businesses into the formal economy, the directive may lead to their closure or they will regroup to avoid the enforcement of this directive.

Erosion of trust, compliance

Government interventions can lead to a significant erosion of trust between suppliers, retailers, and consumers.

When businesses feel that they are being unfairly treated or regulated, they may become resistant to compliance, leading to further complications in the supply chain. This can create an environment of distrust, where businesses may seek alternative, potentially illegal, means to operate. The result is a fragmented market that is difficult to regulate and monitor.

Increased costs, inefficiencies

Imposing regulations on supply chains can lead to increased costs for suppliers and retailers. These costs often trickle down to consumers in the form of higher prices. Formal retailers may face increased operational costs due to the loss of suppliers who have opted to bypass the informal sector.

Additionally, the government may need to increase oversight and regulatory compliance measures, further adding to operational costs. In a fragile economy, these increased costs can be devastating.

Stifling innovation, competition

A healthy economy thrives on competition and innovation. By favouring formal retailers, the government may inadvertently stifle competition from the informal sector, which often operates with lower overhead costs and greater flexibility.

The ability of informal businesses to innovate and respond rapidly to consumer demands is a crucial aspect of a dynamic economy. Government intervention can lead to a homogenisation of the market, reducing options for consumers and limiting the diversity of products available.

Short-term solutions vs sustainability

Government interventions often focus on short-term solutions rather than addressing the underlying issues facing the economy. While the intention behind regulating supply chains may be to stabilise the retail sector, it does not address the root causes of its challenges, such as inflation, currency instability, and lack of access to capital.

Sustainable solutions require a comprehensive approach that includes support for both formal and informal sectors rather than punitive measures against one or the other.

Role of informal retailers

Informal retailers, such as tuckshops, contribute significantly to the economy by providing affordable goods and services to both high and low-income communities.

They often serve as the first point of contact for consumers and fulfil a gap that formal retailers may not adequately address. By sidelining these businesses, the government risks alienating a substantial portion of the population that relies on them for their daily needs.

Instead of blaming informal retailers for the collapse of the formal retail sector, government should explore collaborative approaches to integrate these businesses into the formal economy.

Formal and informal retailers can co-exist side by side the economy when some of the reasons mentioned above why formal sector retailers are failing, are dealt with.

Global trends, lessons learned

Looking at global trends, many countries have recognised the importance of the informal sector in their economies. Rather than attempting to eliminate or regulate it out of existence, successful governments have sought to create an environment where both formal and informal sectors can coexist and thrive.

For instance, in countries such as India and Brazil, initiatives have been introduced to support informal businesses through access to credit, training, and market opportunities.

These approaches have proven more effective in fostering economic growth and stability than announcing punitive measures.

Here are specific examples from India and Brazil that illustrate this approach:

India: The Pradhan Mantri MUDRA Yojana

In India, the government implemented several initiatives aimed at supporting informal enterprises. One standout programme is the Pradhan Mantri MUDRA Yojana (PMMY), launched in 2015. This scheme aims to provide micro-financing to small businesses and entrepreneurs, particularly those in the informal sector.

l Micro finance support: Under PMMY, loans up to (rupees) 10 lakh (about

US$13 500) are provided to small businesses without requiring collateral. This access to credit has empowered countless informal retailers, allowing them to invest in inventory, improve their operations, and expand their businesses and some of them graduating to becoming formal sector businesses.

l Skills development: The initiative also emphasises skill development through various training programmes, ensuring that informal sector workers gain essential skills to enhance their productivity and competitiveness.

This dual focus on financial support and skills enhancement has helped many informal businesses transition into the formal economy.

Digital inclusion: Furthermore, the Indian government has promoted digital payments through initiatives like the Digital India campaign, encouraging informal businesses to adopt digital payment systems. This not only increases transparency but also helps informal retailers access larger markets.

The simples nacional tax regime

In recognising the importance of the informal sector, Brazil has implemented policies to facilitate its growth and formalisation. One of the most notable initiatives is the Simples Nacional tax regime, introduced in 2007.

Simplified taxation: Simples Nacional allows small businesses to pay a single tax that combines several federal, state, and municipal taxes. This simplification reduces the compliance burden on small and informal businesses, making it easier for them to operate legally.

Support for formalisation: The programme specifically targets micro and small enterprises, which often include informal businesses. By providing a more manageable tax structure, the Brazilian government incentivises informal businesses to formalise, thereby enhancing their access to credit, market opportunities, and social benefits.

Promotion of entrepreneurship: Brazil has also launched various entrepreneurial programmes aimed at promoting small business development. For instance, initiatives that provide mentoring, training, and access to markets have been implemented to help informal retailers grow and transition into formal enterprises.

The examples from India and Brazil illustrate that effective government strategies can support the informal sector rather than marginalise it.

By providing access to financial resources, simplifying regulatory frameworks, and enhancing skills, both countries have fostered environments where informal businesses can thrive.

These approaches not only contribute to economic growth but also promote social inclusion, highlighting the importance of recognising and empowering all sectors of the economy.

Instead of imposing restrictive measures, governments should learn from these successful models to create collaborative frameworks that allow informal and formal sectors to co-exist and contribute to a vibrant economy.

Collaborative approach

In Cluster Theory, Harvard Business School Professor Michael Porter, advanced the notion that a vibrant sustainable economy needs to have linkages between big corporates and micro, small and medium-sized enterprises.

Instead of imposing restrictions on the informal sector, governments should seek to collaborate with informal retailers and suppliers.

This could involve creating pathways for formalisation that respect the unique characteristics of informal businesses.

For example, providing training and resources to help informal retailers comply with regulations can facilitate their integration into the formal economy without jeopardising their existence.

A collaborative approach fosters goodwill and builds a more resilient economic ecosystem.

A caution against intervention

In conclusion, while the challenges facing Zimbabwe's retail sector are significant, government intervention in supply chains and value chains is not the solution.

The directive to bypass the informal sector in favour of formal retailers is likely to exacerbate existing problems, leading to inefficiencies, increased costs, and further marginalisation of informal businesses.

A more effective approach would involve recognising the value of the informal sector, fostering collaboration, and addressing the root causes of the challenges faced by the retail sector.

By allowing market dynamics to function freely and supporting all sectors of the economy, the government can create a more stable and prosperous environment for all stakeholders.

Ndoro-Mkombachoto is a former academic and banker. She has consulted widely in strategy, entrepreneurship and private sector development for organisations that include Seed Co Africa, Hwange Colliery, RBZ/CGC, Standard Bank of South Africa, Home Loans, IFC/World Bank, UNDP, USAid, Danida, Cida, Kellogg Foundation, among others, as a writer, property investor, developer and manager. — @HeartfeltwithGloria/ +263 772 236 341