ZIMBABWE’S land issue has long been at the centre of its politics, yet it remains unresolved after decades of reform attempts.

From colonial times to the present, the question of land ownership has shaped not only the country’s agricultural productivity but also its economic performance and political stability.

The Fast Track Land Reform Programme (FTLRP) of 2000 was supposed to correct colonial imbalances. At independence, around 6 000 white farmers controlled 45% of arable land, while 700 000 black farmers shared the remaining 55%.

However, the extent to which the FTLRP addressed this imbalance remains unclear. Many believe that white farmers were largely replaced by political elites, or that the redistribution occurred without the necessary agrarian infrastructure to support new landholders.

Regardless of the view, it is evident that the promised benefits of land reform have yet to materialise.

One constant truth about Zimbabwe’s land policy is its use as a political "carrot" by the Zanu PF government. Whether amid economic decline or political challenges, land tenure is frequently invoked to rally support.

This was particularly evident in 2000, when a politically weakened President Robert Mugabe launched the FTLRP to appease war veterans and secure their backing.

Forty-four years after independence, land remains a political tool for Zanu PF. In times of economic instability or waning political support, land policy is dangled as a political victory with supposed economic benefits.

This approach, however, has resulted in piecemeal, tactical policies that have yet to deliver the sustained economic development Zimbabwe desperately needs.

The most recent announcement from the government made it clear that communal farmers under traditional chieftainships would remain exempt from the new land documents.

The 1982 Communal Land Act continues to bind communal farmers to a system in which all land is vested in the President, who holds it in trust for the people.

Chiefs, headmen, and village heads are granted authority to administer this land, effectively trapping rural farmers in a system of usufruct rights — they can use the land, but they cannot own it.

Critics argue that offering freehold tenure to communal farmers carries the risk that they might borrow against their farms and lose them to banks in the event of defaults.

While this risk exists, it must be considered in light of the displacement many rural families already face from miners and other actors given government permission to seize land.

Without ownership, communal farmers — especially women and young people —remain vulnerable. Freehold tenure could change this dynamic, allowing protective measures to be enforced through financial regulation.

Additionally, banks are more likely to focus on lending than on repossessing small farms, which are not particularly lucrative in real estate. Either way, the Communal Land Act needs urgent revision to address these growing challenges.

Following the FTLRP, an audit by Agritext officers was ordered, but it mostly served to formalise the chaotic "jambanja" land reform led by war veterans.

Since then, the glaring absence of a comprehensive, transparent, and accessible land audit remains. Without such an audit, the redistribution process initiated by the FTLRP has never been fully evaluated.

Who received the land? Is it being used productively? How many beneficiaries still hold their land, and under what conditions?

These crucial questions need answers before any further reforms are considered. Continuing to implement new land policies without a comprehensive audit is simply rubber-stamping the failures of the past.

Moreover, the recent policy announcement still falls short of guaranteeing bankability.

Despite being intended to enhance tenure security, the new land documents come with restrictions that undermine their effectiveness.

The condition that land can only be sold to indigenous Zimbabweans limits its market value, making it less attractive as collateral for banks.

This restriction will continue to stifle access to capital, leaving many farmers vulnerable to high-interest loans that reflect the marketability risk. Furthermore, these documents, not being true title deeds, are susceptible to future policy changes, adding another layer of uncertainty.

Another major obstacle to the success of the current policy is the lack of an electronic land registry and the high cost of conducting land surveys.

For the government’s policy to work, a comprehensive survey is needed to demarcate land, resolve disputes (such as overlapping claims), and establish clear records of ownership.

However, the cost of such a survey has been conspicuously absent from recent national budget statements. Without proper funding, any attempt at a survey will likely be disorganised and skewed in favour of the politically connected, further disenfranchising ordinary citizens.

Even if a survey were conducted, the reliance on out-dated, manual processes could open the system to manipulation. Those with political influence or financial clout could easily tamper with records, distorting land allocations to their advantage.

This undermines the credibility of the entire reform process, which needs to be transparent and equitable to succeed. Women, in particular, are at risk of exclusion due to limited access to information and the lengthy, inaccessible bureaucratic processes involved.

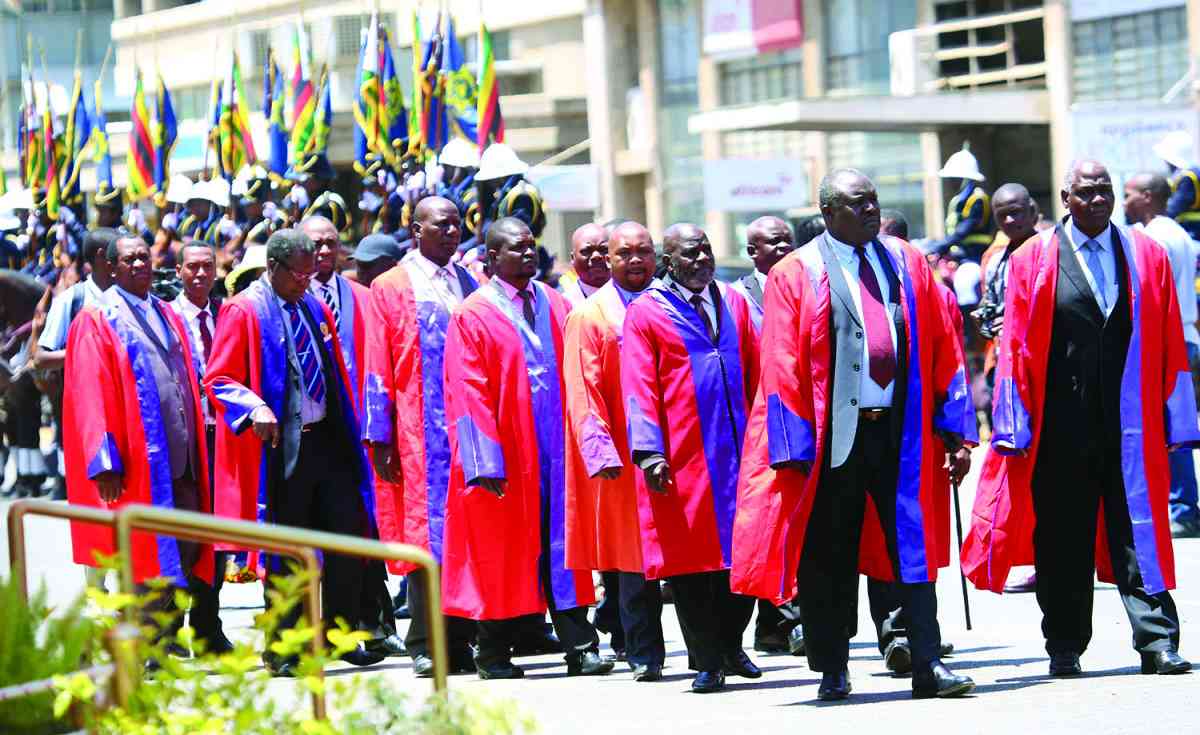

One of the most puzzling aspects of the latest policy announcement is the appointment of Defence minister Oppah Muchinguri-Kashiri to lead the initiative, rather than the Lands minister.

This raises serious questions about the motivations behind the reform. Land reform is an economic and agricultural issue, not a security one. So why is the Defence minister in charge?

The answer may lie in Zimbabwe’s history of land reform. During the FTLRP, key figures like Chenjerai Hunzvi and Joseph Chinotimba led war veterans in land occupations, which helped consolidate Mugabe’s political power.

By placing the Defence Minister at the helm of land reform, President Emmerson Mnangagwa may be trying to strengthen his own position by aligning with the military, a critical player in Zimbabwean politics.

This suggests the current reforms may be more about political consolidation than genuine agricultural or economic transformation.

For Zimbabwe to unlock the full potential of its agricultural sector, urgent agrarian reform is needed. This reform must go beyond land redistribution to tackle broader challenges, including market access for smallholder farmers, investment in infrastructure (such as irrigation, roads, and storage facilities), and research into sustainable farming practices and climate adaptation.

Agrarian reform must also include building inclusive financial systems that provide affordable loans, grants, and technical assistance to farmers. Without this, Zimbabwe’s land reforms will continue to fall short of delivering the economic growth and food security the country desperately needs.

Finally, true success in land reform can only be achieved through a land audit and the issuance of proper title deeds, not just “documents” as described in recent policies.

Title deeds provide the security necessary for long-term investment and development. They allow landholders to use their land as collateral for loans, unlocking capital for productivity improvements.

A "document," on the other hand, offers no such certainty, as it remains subject to future policy changes, potentially limiting the holder’s freedoms.

Zimbabwe’s land issue remains a political tool, wielded by the government without addressing the deeper systemic problems. Without comprehensive land audits, transparent tenure reform, and agrarian development, Zimbabwe’s land policies will continue to benefit the politically connected while leaving ordinary farmers and rural communities behind.

For real progress, Zimbabwe must move beyond political rhetoric and implement a truly inclusive and transparent land reform process that gives all citizens, particularly the marginalised, and a stake in the future.

Mutambasere is a development economist at The Africa Centre for Economic Justice.