What could be so rare and valuable that it would be worth going all the way to the Moon to get some?

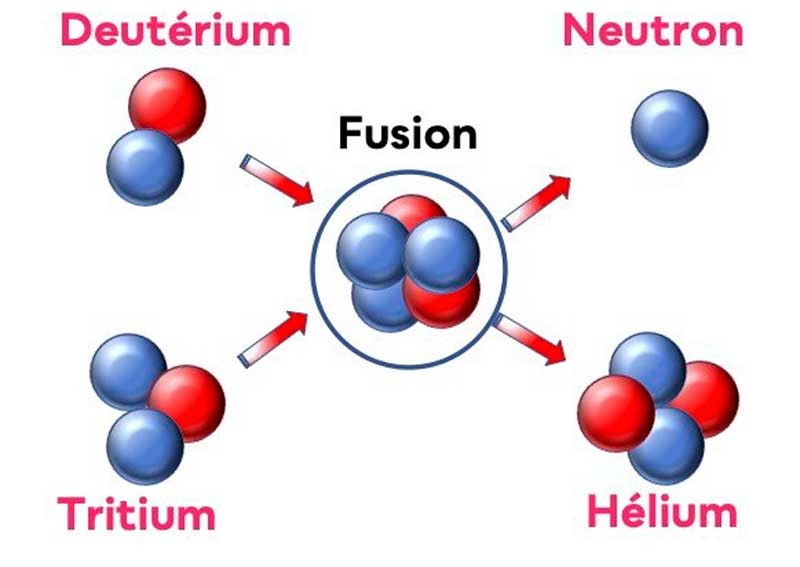

If you ask Google, it will tell you helium-3, an isotope of helium that is the ideal fuel for nuclear fusion reactors. It’s very rare on Earth, but Nasa, the US space agency, estimates that there is a million tonnes of it on the Moon.

However, there are no fusion power plants yet. They are still ‘thirty years away’, as they have always been. So what’s the rush, then?

Monday morning’s launch of the new Peregrine lunar lander, with a robotic rover aboard, is the first of half a dozen ‘mining’ missions scheduled for the Moon this year. Some are funded by Nasa’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services initiative (CLPS); others are private start-ups that sense a business opportunity. But mining? Really?

No. Mining of a sort is involved, but the ‘miners’ will be seeking basic resources like water and oxygen that are free and universally available on Earth. On the Moon they will be digging into the ‘regolith’ (the lunar equivalent of soil) and into the ice they think is hidden in various craters that are never exposed to direct sunlight.

The various landers and orbiters flocking to the Moon this year — SLIM, Peregrine, Nova-C, VIPER, Blue Ghost, etc., just to mention the American ones — will be checking out various locations for lunar bases and accessible resources, because by next year there will be people there — and soon they’ll be staying for good.

There won’t be a continuous human presence next year or the year after, but there will be lots of coming and going, and there will be permanent manned bases before the end of the decade.

That means a whole infrastructure has to be put in place in at least two separate versions, one for the US and its friends, one for China.

- Re-imagining the workplace: Google and other company visions

- Letter to my people: Skeletons tumbling out of closets

- Local firms fail Tanganda test

- In Conversation with Trevor: ICT guru Stafford Masie speaks out

Keep Reading

We know that there is frozen water in some places on the Moon (the Indians found it years ago), but we don’t know where or how much. Some people think it may be possible to get moisture out of the regolith anywhere, but maybe not.

Small nuclear reactors will give you electricity to split water, and that will give you oxygen to breathe and hydrogen for fuel, but there are countless details to figure out. Can hydroponics (and maybe meat grown on lattices) provide most of your food, or will most of it have to be brought from Earth?

If the sources of abundant ice are few and far between, who gets the good ones? Will lunar dust get into everything and gum up your machines? This is a whole world, albeit a small one (about the same area as Asia minus the Middle East), and there are a thousand things we don’t know about it.

So why are we all going back there after fifty years when we practically ignored the place? Not just the Chinese and the Americans, either, but soon enough the Indians, the European Union, and probably the Japanese and the Russians as well. Not for ‘science’. Not for profit either, although lots of money will be made. One word: prestige.

Apple TV+ has made a science fiction series called ‘For All Mankind’ based on the simple counter-factual that the Russians got to the Moon first in the 1960s. The ‘space race’ therefore continues credibly for decades, although neither side is making any money out of it, or gaining any military advantage.

The fourth season is just finishing and our heroes are on Mars by now, although it’s still only 2003 in film time. Prestige alone was a sufficient motive to get them there — and similarly in real time what is finally putting manned space travel beyond Earth orbit back on the agenda is the emergence of a plausible Chinese rival to the United States.

There are no big strategic or commercial advantages to be had in this competition for prestige, but there may be disputes over the best sites for bases. What worries the diplomats is that the treaties banning annexation or legal ownership of lunar territory are unratified or unclear.

Scientists, on the other hand, worry that the best sites for their work may be pre-empted by ‘miners’ digging for ice and other physical resources.

“We are not trying to block the building of lunar bases,” explained Prof. Richard Green of the University of Arizona. “However, there are only a handful of promising sites there and some are incredibly precious scientifically. We need to be very, very careful where we build our mines and bases.”

Fair enough, but long may the competition for prestige continue. It’s the best kind of rivalry by far.

Dyer is a London-based independent journalist. His new book is titled The Shortest History of War.