AS a freelance health science journalist, I have been investigating the hazards of silica dust exposure and its devastating impact on artisanal miners in Zimbabwe. My search for answers led me to Bruce Mhondiwa, a renowned expert in occupational health. He is also the medical superintendent for Kwekwe General Hospital.

We discussed the burden of silicosis in the Midlands, particularly in Kwekwe, and the challenges of managing this incurable disease. In Zimbabwe’s mining communities, a silent killer is claiming lives. Silicosis, an occupational lung disease caused by inhaling silica dust, is gathering pace silently as young people flock to informal mining.

Mhondiwa said: “It’s a major concern in our mining communities, particularly among artisanal miners who often work in poorly-ventilated environments.

“By nature, or say, lack of awareness, lack of protective clothing puts miners at risk. In our province, a significant concern for miners, particularly artisanal miners, is the lack of proper protective clothing. This increases their risk of contracting occupational diseases.

“Essential protective gear, often missing, includes dust masks to prevent silica dust inhalation. The miners also lack gloves to prevent hazardous material from making skin contact.

“They don’t use safety goggles to protect eyes from debris and dust. They normally don’t wear steel-toed boots to prevent foot injuries. At times, they don’t even have overalls or work suits to prevent skin exposure.

“Without proper protection, miners are more likely to contract silicosis from inhaling silica dust. They are at risk of tuberculosis (TB) from inhaling TB bacteria. HIV, mainly through unprotected sexual exposure to infected bodily fluids.

“Artisanal miners are especially vulnerable due to their informal work arrangements and limited access to resources. They hardly have time outside work,” he added.

- Mob fatally assaults thief

- Boy (11) electrocuted

- Corpse found floating in Kwekwe River

- UPDATED: Fourteen pupils injured in school collapse

Keep Reading

As we delved deeper into the issue, Mhondiwa revealed the alarming reality in Kwekwe, a mining town in the Midlands province.

“Unfortunately, Kwekwe has a high burden of silicosis patients. We have lost 48 patients from last year to date. We currently have admitted silicosis patients in various stages,” he said.

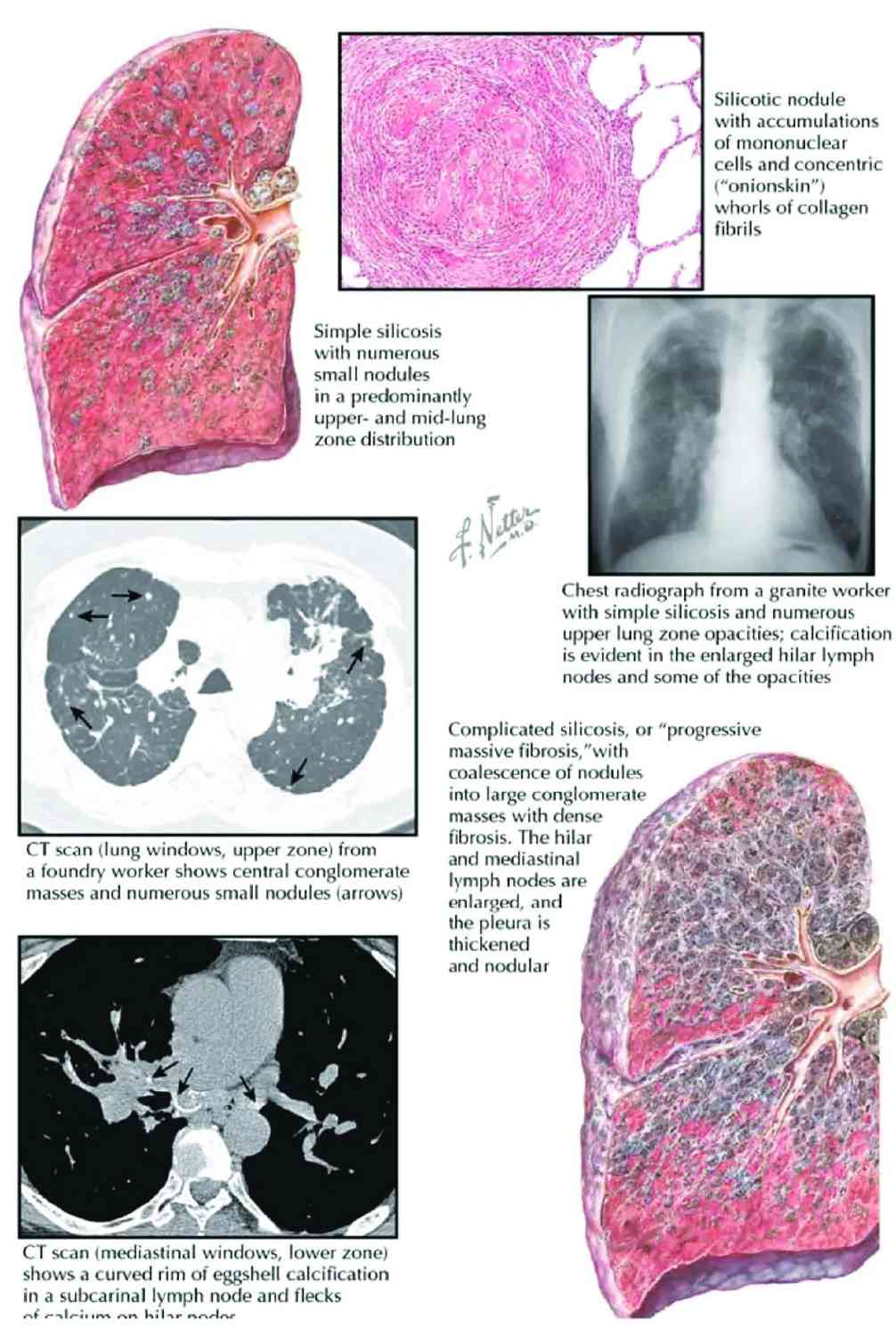

“Silicosis has stages, and those with early stages can survive if they change their lifestyle and work in a dust-free environment doing light duties.

“However, those with late stages, characterised by progressive massive fibrosis, will rely on oxygen therapy. The stakes are high, and the numbers are staggering. But what can be done to prevent silicosis?”

Mhondiwa emphasised the importance of protective measures. “Miners can reduce their risk by wearing protective clothing and masks, working in well-ventilated areas, and undergoing regular medical check-ups,” he said.

“By nature of the work, miners are away from home and hardly find time. Silicosis is often complicated by co-infections, particularly tuberculosis (TB) and HIV.”

Mhondiwa noted that the triple infection of HIV, TB, and silicosis is particularly devastating.

“HIV compromises the immune system, making it harder for the body to fight off TB and silicosis. It’s a major challenge,” he said.

To address this challenge, Mhondiwa stressed the need for community-based initiatives, government support, and a comprehensive national strategy for managing occupational lung diseases such as silicosis.

On the palliative care for discharged patients, Mhondiwa said: “As medical practitioners, it is our duty to ensure that our patients receive the best possible care, even when their condition is terminal.

“For silicosis patients, palliative care is crucial in managing their symptoms and improving their quality of life.

“At Kwekwe General Hospital, we have a policy of discharging palliative patients, including those on oxygen therapy. Yes, we do give them oxygen concentrator to continue their care at home.

“This allows them to spend their remaining time in the comfort of their own homes, surrounded by loved ones.

“We work closely with the patients' families to ensure that they receive the necessary support and care. Our team of healthcare professionals also provides regular check-ups and support to ensure that the patient’s symptoms are well-managed.

“By discharging palliative patients, we are not giving up on them, but rather, we are giving them the dignity and comfort they deserve in their final days.

“Silicosis is a preventable disease. We need to take collective action to protect the health and well-being of our miners. It’s a matter of life and death.”

Mhondiwa advised people to always seek medical attention instead of self-diagnosing and self-treating.

“Many patients report late to the hospital after attempting self-treatment, which can lead to severe complications and poor health outcomes,” he said.

“The problem with self-diagnosis is that you end up prescribing yourself the wrong medicine, sharing medicines, and even using expired ones,” Mhondiwa warned.

“People should not buy drugs on the streets. Always visit a clinic near you when ill.”

The doctor’s warning comes as a timely reminder of the importance of seeking professional medical advice. By visiting a clinic or hospital, patients can receive accurate diagnoses, proper treatment, and personalised care.

As our conversation came to a close, Mhondiwa conveyed a powerful message.

“Remember, your health is worth more than a Google search. Seek professional medical attention today!”

While the Midlands province is rich in natural resources, boasting 18 mined minerals, including gold, and hosting 33% of the Great Dyke, it is a hotbed of silicosis.

As a hub of activity and migration, the province is also vulnerable to risky behaviour. With its diverse economy spanning Regions II to IV, from mineral resources to a strong agricultural sector, the Midlands province is an attractive destination.

However, this also increases the risk of HIV, TB, and silicosis transmission, particularly among artisanal miners.

- Email: [email protected].