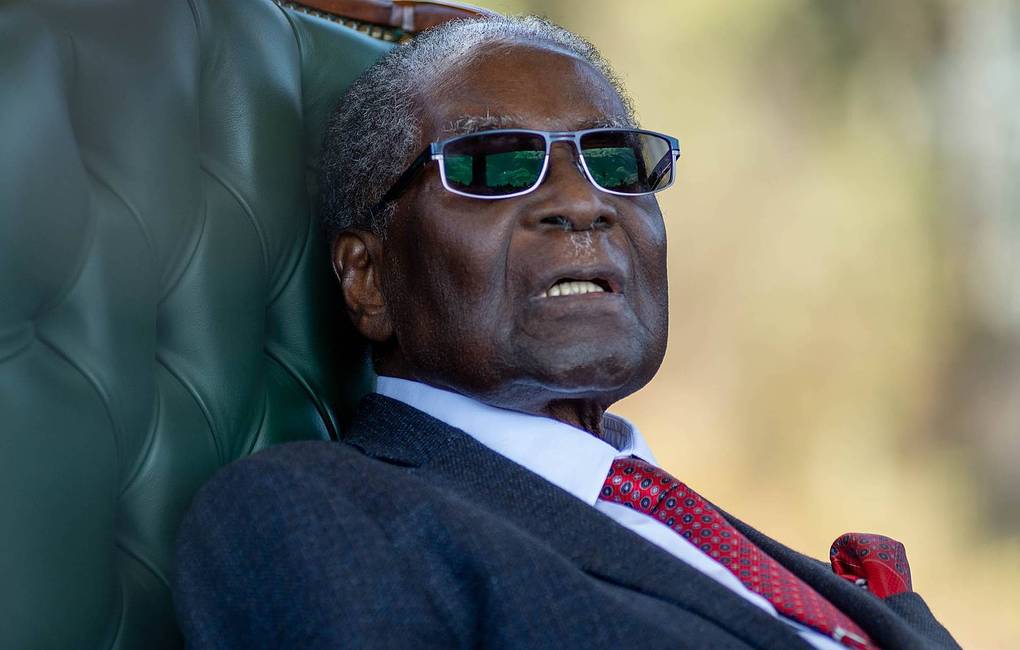

SYDNEY KAWADZA ZIMBABWE’S education system, a source of pride for citizens and envy of many across the continent under the late former President Robert Mugabe, is now on a downward spiral seeking urgent intervention.

education system, a source of pride for citizens and envy of many across the continent under the late former President Robert Mugabe, is now on a downward spiral seeking urgent intervention.

The drastic drop in the quality of education is mirrored in the state of the economy and a deterioration of the standards of living for the majority of Zimbabweans.

This has resulted in a massive exportation of high quality human capital to other countries across the globe.

Education experts are also accusing President Emmerson Mnangagwa’s administration of ignoring the critical sector, destroying a legacy built over decades including during the colonial era.

Decades of economic downturn, maladministration, corruption, neglect and poor funding has seen Zimbabwe’s education sector once considered the best in Africa facing a dramatic decline in standards over the years.

The situation, coupled with serious brain drain, poor remuneration for teachers, perennial job action, obsolete infrastructure and equipment as well as the ravages of the Covid-19 pandemic has left the sector on the throes of death.

Speaking in various interviews, academics and experts painted a gloomy picture of Zimbabwe’s education system calling on the government to take urgent action against the rot.

- Chamisa under fire over US$120K donation

- Mavhunga puts DeMbare into Chibuku quarterfinals

- Pension funds bet on Cabora Bassa oilfields

- Councils defy govt fire tender directive

Keep Reading

They noted that Zimbabwe’s future generations risk a bleak future where their qualifications – academic and vocational – will never be recognised across the world.

Former education minister during the Government of National Unity (GNU), David Coltart said although the sector remained one of the best in Africa, it faced a difficult future after years of decline.

He called for a radical mind shift to restore the sector.

“Mnangagwa has appointed a succession of ministers who, quite frankly, have little interest in education. It is clear that it is not

a priority of his government.

“Overall, we have seen a dramatic decline in the education sector since the advent of the Mnangagwa government. Robert Mugabe was a teacher himself and he understood the importance of education,” Coltart said.

Mugabe, Coltart said, did what he could to ensure that the education system was adequately funded.

“Mnangagwa, in my view, does not have the same appreciation for education or the understanding that Mugabe had,” he added.

Coltart said there is no doubt that the education system has been seriously undermined in the last 15 to 20 years by strikes coupled by a mass exodus of teachers during the period 2007-2009.

Many teachers went to South Africa and never came back which decimated the education system that had for decades been touted as the best on the continent.

Approximately, 20 000 teachers deserted the profession for other jobs during the period.

The former minister said teachers were paid starvation wages that have triggered job action and lower output.

Coltart, however, criticised Mugabe for focusing mainly on academic education.

“The colonialists had a very good system of vocational, practical education that Mugabe did not and that was undermined in the 1980s heavily criticised by educationists at the time. In fact, that was the focus of the Nziramasanga Report published in 1999 which established that there was a serious imbalance,” he said.

The Nziramasanga, in part, recommended the promotion of practical skills in primary school, introduction of vocational education at that stage followed by same training in secondary schools.

This, according to the report, would lead to a range of qualifications in different occupation areas – professional, academic, practical and technical.

Coltart said the sector also lacked investment, progressively and in real terms, in the 1990s and 2000s, when Zimbabwe ceased getting international aid making the situation dire.

Education deteriorated rapidly in 2005 through to 2008 as teachers’ salaries declined leading to a mass exodus of teachers.

He said he took over an education system in 2009 during the GNU with 8 000 government schools closed while more than 100 000 teachers were on strike.

“The public examinations which were written in November 2008 were not even marked and the textbook-pupil ratio was atrocious, down to 15 pupils to one textbook at best.

“In many schools the only textbook was the one that the teacher had and during my tenure in 2009 through to 2013, we managed to stabilise the education sector,” Coltart said.

“We got 15 000 teachers back to service through an amnesty, and we got the textbook pupil ratio down to one to one and started working on the recommendations by the Nziramasanga Report.”

Coltart also accused Zanu PF of frustrating these efforts during the GNU and the curriculum issue was not adequately addressed adding that the teaching system has a heavily demotivated staff attracting those who would have failed to get into other disciplines.

He added that the government needed to change its attitude towards education, improve teacher training facilities while raising education requirements for people to become teachers.

“There is a need for a variety of incentives once people have trained as teachers. The status of the teaching profession needs to be raised so that we attract the best brains into the teaching profession,” he said.

Coltart said it was also fortunate that Zimbabwe’s education system remained very good in terms of the actual standards arguing that pupils who get to Advanced Level have a chance of making it outside Zimbabwe.

Tswane University of Technology department of public management’s Professor Ricky Mukonza said the education standards reflected a decline in social life in Zimbabwe.

He said chief among the reasons for the decline was lack of resources.

“For example, I would pick an investment area in the ICT component of that sector. Investment in modern equipment and technologies that will allow pupils to learn from relevant technologies.

“So indeed, the quality of education in Zimbabwe has gone down. That is a cause for concern because the education sector is quite critical for the economy. That sector is critical for human development and Zimbabwean society. Something needs to be done to ensure that it returns to its former glory,” Mukonza said.

The Pretoria-based academic said the decline in education standards was not isolated as it indicates a general decline in standard of life in Zimbabwe.

“What we are seeing is the microcosm of the macrocosm, in the sense that it is a reflection of the decline in Zimbabwean society in general.

“If things are not good in the economy, there is no way that an investment can be made in such a sector. This appears to me as misplaced priorities on the part of the government,” he said.

Mukonza acknowledged the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic to education adding that the government had failed to invest in technology investment in primary and secondary schools affecting the transition into online learning.

He however, argued that while Mugabe’s legacy was under threat, the decline did not start under the current administration.

“It started under Mugabe because we could see that post-2000 and the standard of education kept going down after Mugabe left, and sadly, the so-called new dawn has not done anything to ensure that the situation improves.

“I would say one of the key challenges is lack of funding and investment in the education sector.”

Another former cabinet minister and renowned academic and one of the architects of the education revolution, Fay Chung concurred that Zimbabwe educational quality had deteriorated for most schools over the past 20 years.

She, however, said despite the deterioration, some schools have managed to retain high standards.

“This means wealthier Zimbabweans have managed to maintain the quality of education for their children in trust schools.

“However, more than 70% of Zimbabweans are poor and these include the teachers. They are not managing very well. An economic development solution is essential rather than demanding payment in US dollars,” Chung said.

“With subdued production and failing exports Zimbabwe does not have enough US dollars to pay the large civil service, including the teachers.”

She also argued that the colonial education system was good for 4% of the population leading to questions on how Zimbabwe can cater for the majority.